Mining companies are jostling to negotiate lithium deals under a new government model in Chile, home to the world’s biggest reserves of the metal that’s a key component in electric-vehicle batteries.

To meet the demand, authorities are well advanced in work to identify new extraction areas and are compiling bidding rules for contracts to explore and possibly mine them, Karla Flores, head of InvestChile, said in an interview.

More than 50 firms from around the world have expressed interest in participating in Chile’s new public-private model, with a roadshow held in Germany and France last month and another planned for Korea, Japan and China in October, Flores said.

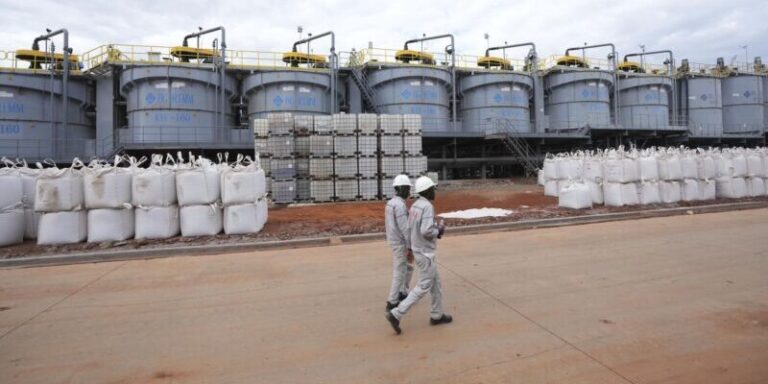

Until now, Chilean lithium production has been limited to two companies working a single salt flat, with the nation’s market share slipping in recent years.

President Gabriel Boric’s solution is a model that will see the state take a controlling stake in operations considered strategically significant while allowing private firms to retain control of projects in non-strategic areas.

‘CATCHING UP’

Countering opposition arguments that a state-led industry would erode competitiveness, the government says its model is the best way to boost sustainable production in a nation that already classifies lithium as a strategic resource controlled by the state.

“We are catching up in an accelerated way but also a correct way,” Flores said from the Santiago offices of InvestChile, which is part of the Economy Ministry. “That’s a benefit to investors — to have clarity and equal opportunity.”

Bidding for the exploration contracts is scheduled to take place early next year. But coming up with selection criteria is no easy task given the number and diversity of proposals — from extraction all the way to producing value-added products.

The two state companies tapped to partner with private firms, Enami and Codelco, are also still building out their lithium teams and procedures.

“There is a queue of interested parties wanting to negotiate with Enami and Codelco,” Flores said. But first, “there has to be a mechanism that’s objection, clear and equal for all,” she said.

Lingering misconceptions that the new approach is a quasi-nationalization, combined with a lack of definition on how projects will be owned and operated, have kept some investors cautious. That’s despite a steady flow of endorsements for the model — from the mining industry itself to the United Nations.

“This is a well-intentioned strategy that’s been broadly well received,” said Max Vichniakov, founder of Northern Shoreline, which advises resource firms, including explorers in Chile. “But announcing it without specifics translates into more financing risk.”