On the outskirts of El Dorado — heart of Arkansas’ 1920s oil boom — a company backed by Koch Industries is looking to dramatically speed up extraction of a battery metal essential to weaning the world off fossil fuels, while proving naysayers wrong in the process.

Standard Lithium is working on the breakthrough inside a white warehouse near a massive chemical factory run by Germany’s Lanxess that feeds brackish wastewater into the facility.

A cluster of pipes and tanks in the demonstration plant turn brine into a lithium compound within days instead of the year or more that traditional recovery methods take.

The firm is among dozens of companies racing to commercialize technology to extract lithium directly from brine, ushering in a new source to supplement the hard rock mines and huge evaporation ponds that currently supply the battery metal to the world.

The outcome of such efforts is set to shape the industry’s future, bringing either the promise of abundant supply or setbacks that sour investors for years.

The advances are collectively known as direct lithium extraction, or DLE. They promise to be cheaper, faster and greener than traditional lithium production in South America, which holds about half of the world’s reserves of the silvery white metal.

DLE would also unlock new supplies in North America, including recovering the metal out of the salty water produced by oil drilling.

“It’s an evolutionary step in the lithium industry,” Standard Lithium CEO Robert Mintak said in an interview. “If we’re going to have a supply chain that can meet the demands of the lithium industry, DLE will be one of the tools.”

All along the world’s EV supply chain, this new way of mining lithium is being touted as the solution for boosting output while protecting the environment.

Billions of dollars are pouring in to what Goldman Sachs Group calls “potential game-changing technology,” much like shale’s disruptive impact on the oil industry.

Still, some producers and industry experts are sounding caution. Despite a boom in testing and development, these techniques are relatively unproven at scale and perfecting them may take years.

After all, Texan entrepreneur George Mitchell experimented with hydraulic fracturing for decades before finding the right method to economically extract shale gas.

Lithium prices surged to record highs last year as growth in demand from the EV boom saw markets tighten. Prices have since fallen amid a steady stream of new output from Australia, though remain elevated thanks to an upbeat outlook for EV growth. An expected shortfall from 2025 is driving startups, miners and even Big Oil to chase new ways to expand supply.

After years of intense testing and development work, the world is about to find out whether DLE works on a commercial scale.

Oil-and-gas heavyweights like Exxon Mobil Corp. are creating businesses to extract lithium from oil field brine.

Rio Tinto Group, the world’s second-biggest miner, is testing extraction methods in Argentina, where it’s developing a lithium project. Meanwhile, Koch and Chinese EV giant BYD Co. are already marketing DLE technologies.

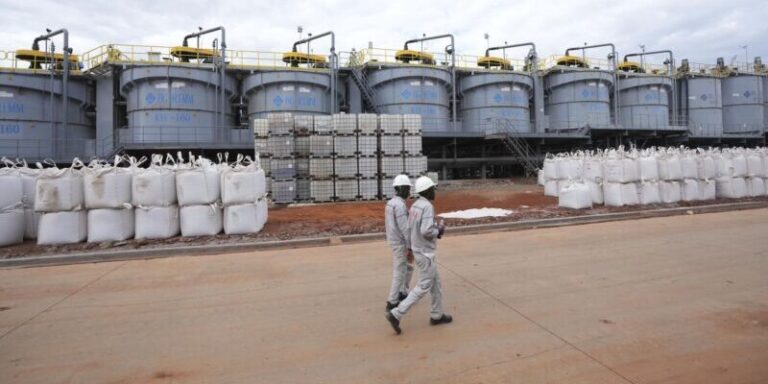

A handful of commercial projects are being built including Eramet SA’s Centenario plant in Argentina, which aims to be fully operational by mid-2025. In China, Sunresin New Materials already operates such plants.

Much of the buzz can be attributed to growing scrutiny of mining’s environmental and social issues.

For years, mines in Chile’s northern desert operated by SQM and Albemarle were seen as the cleanest and easiest way to produce the metal.

They pump up vast amounts of brine from beneath a salt flat, which is then stored in giant ponds for more than a year.

As the water evaporates, the resulting concentrate gets processed at nearby plants and sent to Chinese and Korean battery makers.

As simple as it is profitable, that process uses far less fresh water, chemicals and energy than hard-rock mining as practiced in top producer Australia.

But the evaporation method means billions of liters of brine are vaporized in one of Earth’s most arid places, which some say is a threat to wildlife such as pink flamingos that inhabit its Mars-like landscape.

DLE aims to solve such problems by using equipment like filters and membranes to strip out lithium directly and allow what’s left over to be returned to underground brine lakes.

The process is much faster and uses less space than evaporation ponds. All that would reduce the impact on fragile desert ecosystems — a palatable solution for automakers and their investors as well as local communities and governments.

Bolivia and Chile are making DLE a requirement to tap their lithium riches, a significant move given that the former has the world’s largest potential deposits and the latter has the most economically mineable reserves.

Goldman Sachs estimates that if 20% to 40% of Latin America’s brine projects use DLE, it could boost the region’s lithium output by about 35% from 2028 — or an 8% boost to global supply.

Still, the effects of reinjecting brine haven’t been properly studied, and DLE plant efficiencies need to be weighed alongside the need for more freshwater and energy than evaporation.

The Salar Blanco project in Chile, for example, estimates it will use three to eight times more freshwater.

“The future of DLE technologies is still uncertain, and the long-term feasibility must be evaluated,” SQM said in a written response to Bloomberg questions.

The world No. 2 producer is negotiating a new contract under Chile’s recently announced public-private model that includes a requirement for more sustainable practices.

Joe Lowry, the veteran industry consultant dubbed Mr. Lithium, sees DLE as a technique to unlock new sources in North America. But in South America, it should be seen as a way to enhance rather than replace the evaporation method, he said, estimating that less than 15% of global output will be through DLE in the next decade.

Meanwhile, several oil companies are putting their weight behind efforts to retrieve lithium from oil brine. Occidental Petroleum has said it’s exploring brine-based lithium extraction, while Imperial Oil has a 5% stake in Canadian miner E3 Lithium, which is testing DLE technology in Canada’s oil patch.

Koch, the fuels-to-fertilizer powerhouse, sees direct extraction as a way to help feed a market that’s set to grow fivefold by 2030 as EV adoption accelerates.

DLE is an “easy button, if you will, for the lithium industry to bring on a tremendous amount of supply in regions where you otherwise probably couldn’t,” said Garrett Krall, director of strategic initiatives at Koch Engineered Solutions.

Koch’s technology is on full display at Standard Lithium’s demonstration plant in El Dorado. Koch even invested $100-million in the Canadian company, which plans to start building a commercial DLE facility by the Arkansas site in early 2025. CEO Mintak says he anticipates full production by 2026.

For DLE skeptics, some smaller companies have become lightning rods for questions about the technology.

Short-seller Blue Orca Capital voiced doubts on the viability of Standard Lithium’s technology in November 2021.

About two months later, Hindenburg Research disclosed a short position on the stock in a report critical of the Vancouver-based firm. Standard Lithium called the reports false and misleading.

At an industrial park in Santiago’s outskirts, Summit Nanotech Corp. is readying a facility to test brine from northern Chile.

The Calgary-based firm uses a patented material to absorb the metal and is looking into reinjection methods, applying knowledge gleaned from Alberta’s oil fields.

Direct extraction seems inevitable given the large footprint of evaporation ponds and the community opposition they attract, geoscience director Stefan Walter said.

“It’s going to take time,” he said. “It’s going to be difficult, It’s going to be capital intensive. But all new innovative technologies are kind of like that.”